Designing For People

Guest review by Phillip Hunter

“Design is a silent salesman… contributing not just increased efficiency… but also assurance and confidence.”

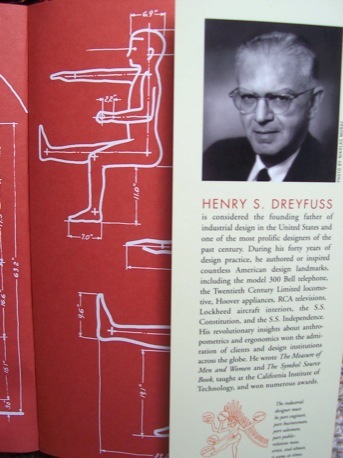

So asserts American Industrial Designer Henry Dreyfuss (1904 - 1972) near the beginning of his 1955 memoir, Designing for People (Amazon: US

Designing for People takes us through Dreyfuss’ decision to establish himself as an industrial designer, expanding from his early career designing theater sets, through the growth of his practice and business and up to the state of industrial design in the early 1950s. The book moves through design thought and philosophy, stories of projects and results, exposition of what the design business is about, and predictions of what industrial designers will work on in the future. He also throws in anecdotal collections of amusing design gaffes and the questions he received over the years. As one would hope, the organization flows smoothly, each section setting the stage for the next.

Dreyfuss’ style is easy and light. Even when making a serious point or giving a detailed explanation of design, he phrases and frames in a manner that allows the reader to comprehend quickly yet deeply:

Q. How do you start an industrial design problem?

A. We begin with men and women and we end with them. We consider the potential user – habits, physical dimensions, and psychological impulses. We also measure their purse, which is what I meant by ending with them, for we must conceive not only a satisfactory design, but also one that incorporates that indefinable appeal to assure purchase. The Greek philosopher Protagoras had a phrase for it, ‘Man is the measure of all things.'”

(Click to enlarge)

Succinct, but packed with meaning that makes careers and businesses, Dreyfuss is not only a good storyteller – a quality we have come to recognize as important in a designer – but he can boil the stories down to important thoughts, plainly stated, which makes for wonderful learning and reinforcement.

As an experienced designer, feelings of encouragement and expansion came up again and again for me as I went through the book. As with Bill Buxton’s Sketching User Experiences

Indeed, many of the lessons he imparts are timeless and he presents them fluidly within the recounting of his professional life. Powerful and clear concepts such as inside out design, user focus, definitions of design success, design ethics, and the role of design working with business are presented again and again in ways that make them resonate more strongly each time.

(Click to enlarge)

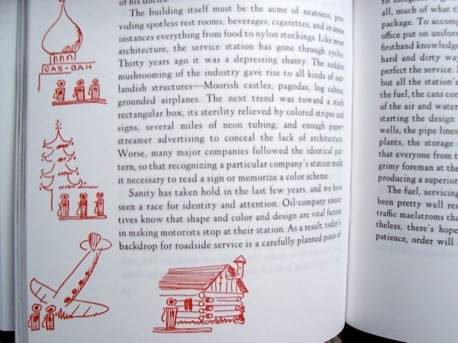

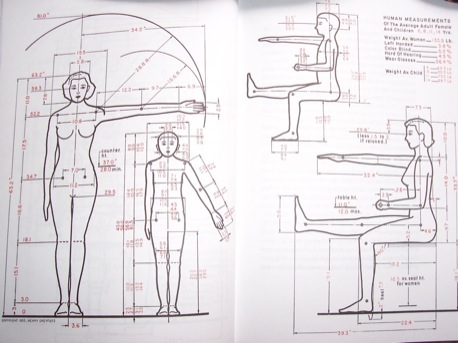

These include classic ideas such as the human models Joe and Josephine (above), “cleanlined”, strong arguments for designers to forge solid relationships with engineers and business managers, and industrial design as “a great equalizer”. His ideas are augmented with photographs, drawings and whimsical sketches providing explanation and insight into his view of the world through the lens of design. Dreyfuss adds further to the sense of “design for the ages” by giving it a history starting with Leonardo da Vinci and moving through Benjamin Franklin, followed by the mid-19th century English Council for the Society of Arts and the American Abolitionist movement.

History is not always kind, of course, and Designing for People feels understandably anachronistic at times, though in ways that support the idea of evolution of design rather than discrediting or marring the primary message. Reading it with today’s sensibilities, one will find some gender and class issues, little acknowledgement of environmental concerns, a fascination with the sterile and modern, and, most sadly, clear evidence that today’s society has lost much of the trust and respect that one could count on in those days.

(Click to enlarge)

Dreyfuss closes with two views of the future circa 2000, one from 1955 and then 1967. He expresses appreciable amazement at what happened in those 12 years, then predicts a sort of Jetsonian future of disposable clothing and linens based on the Space Age occurrences he witnessed. In the midst of starry-eyed musings, he maintains focus on what a designer knows he or she must do:

“The industrial designer’s task is still to relate the inanimate with the animate, to improve a world of non-designer people, non-designer machines and non-designed things, the things you bump your head and bang your shins on, the things that gum up, waste space, cost too much, cost even more to maintain, and are ugly to boot. These are today’s villains and they’ll still be villains tomorrow.” (pg 246)

He goes on to say that technology may make the problems worse, and I daresay we would agree that it has, thus proving his long-lasting wisdom.

(More about Henry Dreyfuss including a list of some of the iconic products he designed.)

You can find Designing for People in Amazon (US

Already read this book? Let us know what you think of it in the comments.

About the Reviewer

Phillip Hunter (@designoutloud) is an interaction designer for voice, desktop, and web applications. He also writes the blog, Design Out Loud.