Meggs’ History of Graphic Design

Review by Patrick Holt

Because the design industry is populated not only by the well-educated, but also by the self-taught and the self-tutored-after-a-mediocre-education (I fall into the latter), it’s likely that many of us missed an opportunity to read Philip Meggs’ A History of Graphic Design (Amazon: US

(Click to enlarge)

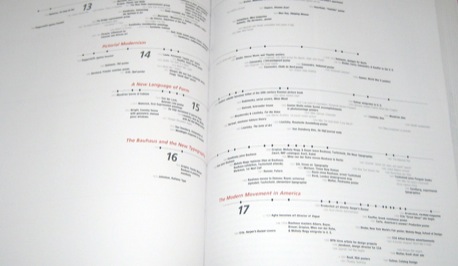

The book begins at the beginning, as literally as can be interpreted: one of the first images is of the more than 10,000-year-old cave paintings at Lascaux, France. Philip Meggs and Alston Purvis then work their way to the near-present through global innovations in symbolic representation, the creation and development of alphabetic systems, technologies that allow the recording and dissemination of information, and the aesthetic developments that accompany them.

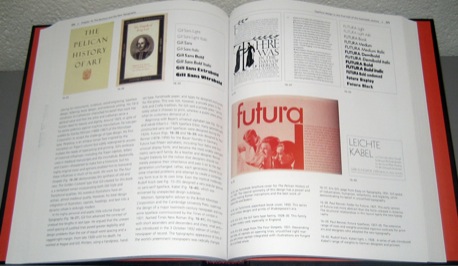

Although it is a history of graphic design, works from other visual arts are addressed whenever relevant, such as the invention and refinement of photography and the influence of modernist painting. And the authors, to their vast credit, define graphic design broadly enough so to include typography, illustration, information design/architecture, environmental design, and motion graphics, providing thorough consideration of each while many books covering graphic design treat these “other” areas as related but less important topics. Perhaps this book should have been called Meggs’ History of the Graphic Arts. Perhaps an industry-wide dialogue on the definition of terms is in order.

(Click to enlarge)

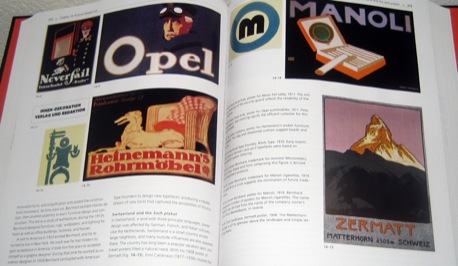

Meggs and Purvis enliven their historical narrative with interesting and entertaining micro-biographies of the figures involved and descriptions of the broader historical contexts that influence and are influenced by graphic design. He quotes a child psychologist’s criticism that early children’s book illustrator Kate Greenaway created “a false and degenerate race of children in art” and laments the mysterious disappearance of the young and talented designer Ethel Reed in 1888. Particularly interesting are cases where design, history, ideology, and personality intersect, as with Jan Tschichold’s change of heart about his New Typography:

“His 1928 book, Die Neue Typographie, vigorously advocated [his] new ideas. Disgusted with ‘degenerate typefaces and arrangements,’ he sought to wipe the slate clean and find a new asymmetrical typography to express the spirit, life, and visual sensibility of the day…

“In March 1933, armed Nazis entered Tschichold’s flat in Munich and arrested him and his wife. Accused of being a ‘Cultural Bolshevik’ and creating ‘un-German’ typography, he was denied his teaching position in Munich… [After moving to] Switzerland, Tschichold began to turn away from the new typography and use roman, Egyptian, and script styles in his design…

“In 1946 he wrote that the new typography’s ‘impatient attitude conforms to the German bent for the absolute, and its military will to regulate and its claim to absolute power reflect those fearful components of the German character [that] set loose Hitler’s power and the Second World War.'”

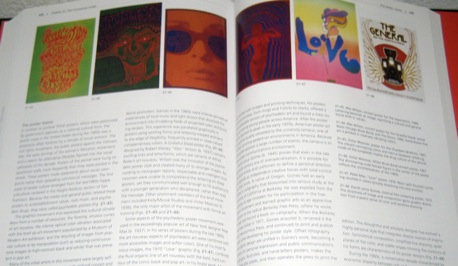

As with most historical overviews, recent history is an awkward thing to discuss. Young voices in design are given as much respect as they deserve; however, one gets the feeling that, though the selected designers may be capable and exemplary, future editions may or may not include any given individual in favor of a more appropriate choice. It is absolutely forgivable not to be clairvoyant, and we should in fact be thankful that the authors forego the hyperventilated tone so prevalent in other books announcing today’s best this or that.

(Click to enlarge)

Web design and Internet-oriented graphic arts are introduced with skillful brevity (they may represent the same philosophical conundrum of graffiti and the like), but the appropriateness of selected examples is doubtful at best. It is likely that, since the newest website represented in the book is from 1996, there has to have been some more recent example that illustrates a given concept more effectively.

Some gaps I wish were addressed more thoroughly include the very brief mention of the posters of the WPA, especially curious considering the book’s emphasis on posters. It could also address more “unofficial” work, including graffiti, posters and flyers for small music venues, and worldwide vernacular design, though these areas might represent a philosophical shift too dramatic to account for. (Another proposal, then: a people’s history of graphic design?) Still, Meggs stated in Heller & Pettit’s Design Dialogues that the book is meant to provide “a basic conceptual overview of the field, a first step in an exploration of design history”, and in this it is entirely successful.

(Click to enlarge)

I sought out Meggs’ History of Graphic Design as a first step on the road toward doing good design rather than just good-enough design. Whether I achieve that goal remains to be seen, but reading this work will no doubt reward any designer with a greater understanding of and appreciation for the rich historical and social contexts of his or her own contemporary work.

Buy Meggs’ History of Graphic Design on Amazon (US

About the Reviewer

Patrick Holt is a sometimes-designer/artist and a graduate of the University of North Carolina’s School of Information and Library Science. His master’s thesis discusses the information age as it is portrayed in science fiction.