The Graphic Eye

Are you a designer because you’re a timid photographer? That seems unlikely. But if you are a designer, you probably carry a camera with you much of the time and have a flourishing Flickr account. You may even use them on your company’s website. But you probably don’t think of yourself as a photographer, do you?

Stefan Bucher is here to persuade you differently. He believes there’s not much difference between you and a professional photographer.

It’s a big claim. It’s true that designers need to assess and employ images every day. Technology has removed the need for photographers to be good at chemistry in a darkened room, and designers are very good at improving pictures that need a ‘little’ help.

Bucher thinks graphic designers should be taking more pride in themselves, and the photographs they take, and he wants to prove it with these 496 images across 210 pages.

Does the book reveal the creative processes of “120 top graphic designers – how they think, their inspirations and obsessions”, as claimed on the back cover? No, it doesn’t. Which is a shame.

But that’s not what Bucher set out to do. There’s only one real example of obsession displayed throughout this book – Stefan Bucher’s determination to take the thousands of photos submitted and shape them into a cohesive experience.

His initial request to 120 designers for them to send their favourite 10 photographs must have seemed very brave when faced with the challenge of moving 800 of them to the trash. This book inevitably tells us more about Bucher than the photographers, and though he never really offers any explanation to his methodology of selection, he’s certainly proud to be a photo–snapping designer.

“With just a bit of editing, our photos don’t look half bad ”

A few themes that emerge across the different designers work – vernacular typography, and charmingly distressed and decaying surfaces are there, of course, but there are also photographers organising the contemporary urban jumble into beautiful compositions of shape and colour.

Bucher enhances this feeling by sequencing images into visual order. A series of related colours, or circular objects make the pages easy to stroll through, but I often found myself forgetting these pictures were not all taken by the same person. That’s where I found myself skipping over pages.

It is a visual treat; inspiring rather than challenging, but there’s no attempt to reveal the promised “creative process, inspirations, and obsessions”.

”All this seems like so much glorious randomness”.

These images have been captured and stolen, rather than engineered by people on their way to somewhere, with several designers simply documenting the means of the travel – Bucher includes his own sequence of vulnerable, shiny airplane wings. They offer a snapshot of people who use their eyes for a living – people fascinated by the visual landscape of their everyday lives. These are not holiday snaps.

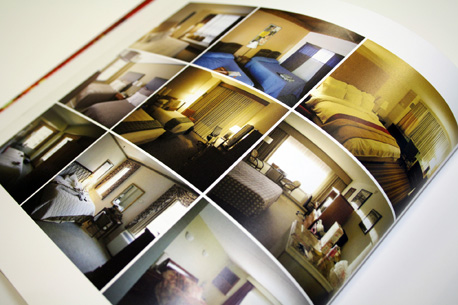

[](/images/2011/02/IMG_1793.jpg) Flicking through to find an example of something that looked like a holiday pictures, I stopped at the images of hotel rooms displaying little joy or any sense of vacation, but full of trepidation. The photographer interprets them as functional, precise, and temporary, despite the lavish soft furnishings, and veneer of comfort. They reveal something about the creator; the celebrated designer and illustrator, Marian Bantjes. We see something of her working life, and her desire to document is habitual. “The first thing I do when I enter a hotel room is take a snap”, she states in the accompanying text. The cumulative effect of these calm pictures, full of understated tension, takes them beyond snaps.

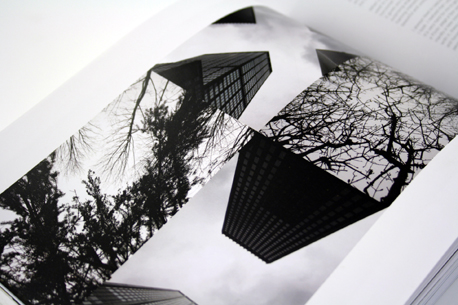

There are a many strong pictures in these pages. Bucher falls into self–deprecation (or is it a plea not to be judged by the same criteria as gallery-photographers?) in his introduction when he states we are all “Dilettantes and amateurs”. Amateurs maybe, but many of the photographers, such as Jakob Trollbäck, Beth Tondreau, and Sean Adams have produced images that question their surroundings with integrity and commitment.

“When you are new to a place, you inspect and look around. As we get used to our environment, our view seems to become more limited and horizontal.”

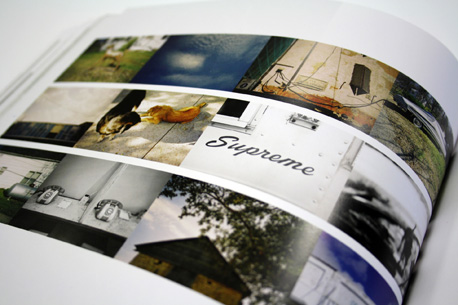

Trollbäck’s images are part of his desire to resist this complacency, while Adams’ Hopelessness sequence is a calm look at the landscapes created by families simply coping, getting by.

Trollbäck’s images are part of his desire to resist this complacency, while Adams’ Hopelessness sequence is a calm look at the landscapes created by families simply coping, getting by.

There may be a lack of hope in Adam’s pictures, but what is also missing from these photographs is missing from many of the other pages.

Where are all the people?

Page after page goes by without a face or body being included. The evidence of man is clearly visible, but man himself has taken the day off. These are all underpopulated towns; cities without a present or a future.

The few faces turn out to be friends of the photographers, and this lack of challenge or confrontation begins to feel like a weakness.

An ability to capture people, and reflect our emotions back to us, is one of the things that sets full-time photographers apart from designer-photographers. Bucher hints at this gulf when he admits that he is “Too shy to take pictures of people".

Many of these designers could become great photographers if only they could dig deeper into the world around them, showing us the things we know nothing about and producing images that spoke to us more directly. Their success in their day jobs is probably going to keep them them too busy to take us deeper into their worlds, but these photographs show a group of people who are intrigued and entranced by the world around them.

Which is what makes them great designers.

The Graphic Eye by Stefan Bucher is published by Rotovision and is available from Amazon (US|CA|UK|DE).

About the Reviewer

Andrew Kingham is a graphic designer based in Brighton, England, and an educator at Goldsmiths, University of London. His website needs updating.