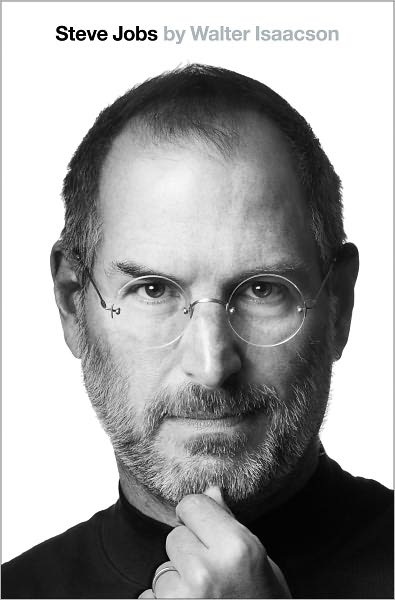

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

This is going to be a short review because there have been so many reviews and commentaries about the Steve Jobs biography by Walter Isaacson (Amazon: US|UK|DE) that it seems there is almost nothing left to say. The question this review sets out to answer is, “why should designers read Steve Jobs’s biography?”

On a personal level, reading through the history of the development of Jobs’s main two successful companies, Apple and Pixar, was fascinating and at times moving, because I’ve worked on so many of the Macs mentioned. I first saw an Apple Lisa (or it may have been an XL) at an architect’s house and was fascinated, especially having whiled away my youth on a BBC Micro and a ZX Spectrum. At college I wrote my first essays on a Macintosh Classic, did my first exercise in Photoshop 2.0 on a Macintosh LC II, my first interactive work after HyperCard using Macromind Director 3.0 on those same LC II’s and, later, my first video and audio work on a Quadra 700. The first Mac I ever owned was a Quadra 650 – the machine that got me through my BA.

I’ve long been excited about the development of 3D animation from very early days and remember being enthralled by the possibilities in a 1984 book that I was given, Computergraphia, that captured some of those early computer graphics years. When I started seeing Pixar’s short films, I knew animation was going to change radically in the years to come. I also realized how crucial good storytelling was to the process – there were a lot of tragically computer science directed “films” (better called demos) floating around in those days.

So much for taking you on a trip down my technology memory lane. Should you care? I think, as designers, most readers will have had similar experiences and, at the very least, it is a nostalgia trip. In some ways reading it also honors Jobs and the things he created that made our current professions possible.

A few months ago I wrote a piece for Core77 that argued that, unlike the hard sciences, design has failed to develop a coherent voice in public discourse. When Steve Jobs died, I realized that he was pretty much it – the one person in widespread public discourse about design who made the case for its value. Whatever you or others may think about his personality, the “reality distortion field”, or Apple’s products in general, there is no debating that an awful lot of non-design people knew of his name, his views and his work. Some of that comes across in the biography, but none of this is really going to make you better and designing things, although it might make you a little more thoughtful as you consider the tips given to him by his father:

“When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.”

The parts of the book that seem to have been less commented on, but that I found more usable in a practical way, were the stories about the interpersonal relationships that made or broke the critical deals that Jobs made. Some of them multi-million dollar ones, such as the deal between Pixar and Disney.

I suspect many designers have somewhat of an aversion to, if not a phobia of, the corporate world and the kind of Big Deal Making that sometimes goes on and that equally seems averse to designers and everything they stand for. While I am sure that Jobs’s approach was pretty unusual, most of the other parties to those deals were more classically corporate folk. For a designer, this book is worth reading just for an insight into how people build and lose companies and client relationships and for understanding how personalities play 90% of the role in working life.

Despite the prevalence of talk about design and Jobs’s deep love and understanding for it, some of the more interesting parts of the book are not about design at all.