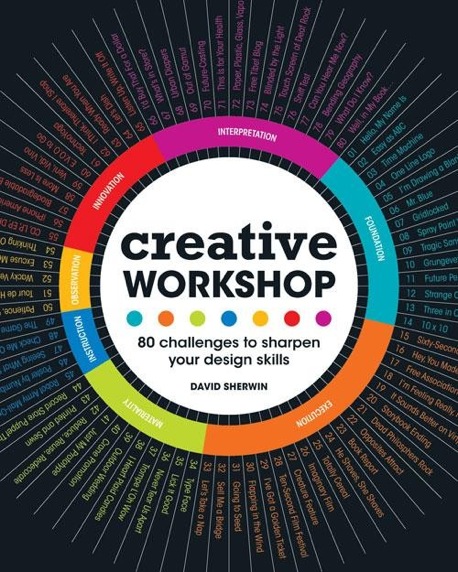

An interview with David Sherwin on Creative Workshop and Success by Design

As part of a new series of interviews with authors, Andy Polaine interviews David Sherwin about the background to the writing of his successful and extremely useful book, Creative Workshop and the development of his new book, Success by Design to be published in November, 2012. David Sherwin has also reviewed several books for The Designer’s Review of Books in the past.

Andy Polaine: What was the inspiration for writing Creative Workshop in the first place?

David Sherwin: The idea for the whole project started when I was trying to write a job description for a designer we needed to hire at my last job. I was looking at hiring sites, seeing what other agencies were listing as critical skills for a mid-level designer. These job descriptions were laundry lists of software tools, coding for various platforms, soft skills like presenting and leading teams… they went on for pages. I couldn’t believe people with all of those skills truly existed out the world, and if they did, why would they be working at these design firms?

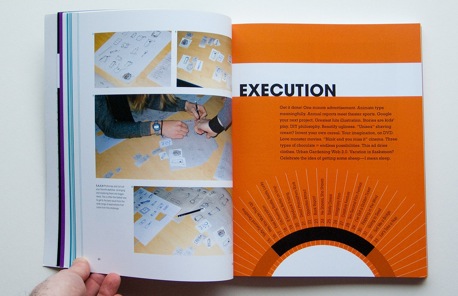

So, to try and clear things up, I sent a survey to creative leaders and thinkers, asking them what they looked for in designers for their studios. And the qualities and skills they were seeking were rarely listed in the job descriptions: big-picture ideation, sketching ideas, communication and collaboration, and resilience and risk-taking. And all of these people I admired in the design community were saying students from design schools weren’t graduating with these core skills.

I was talking about this with my wife, Mary Paynter Sherwin, and we remembered a format that might teach designers these core skills quickly. One of our first roommates post-college was a graduate student in poetry. In the summer of 1999, he took a class called “Instant Thesis, or 80 Works in 7 Weeks,” which was being taught by the poet Peter Klappert. The class explored collage methods, blot-outs, concrete poetry, metric/fixed forms, linked verse, anaphora, dialogue, satire, visual shape, collaborative writing, fixed and loose rhyme schemes, musicality, tone, and dozens of other writing approaches and techniques. Each student was responsible for fulfilling in-class and take-home exercises, as well as coming up with their own exercises that could be shared with the class. Many students found the class to help them build a solid foundation in being a creative writer, most importantly in the areas of resilience and risk-taking. With a little research, we discovered that Peter’s class was adapted from a course taught at the Corcoran School of Art–one where students were only allowed two weeks for creating 80 artistic works!

No one had created a similar approach for teaching core skills in design. So it seemed like a big opportunity, and we dove into figuring out how to make it happen.

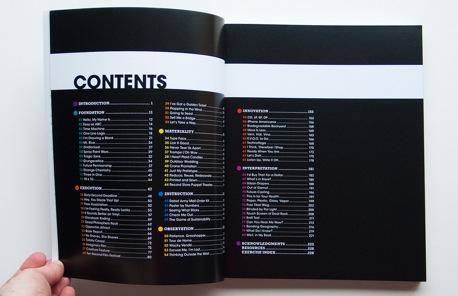

AP: Did you set a goal of 80 challenges and have to find them, or did you already have more and cull them?

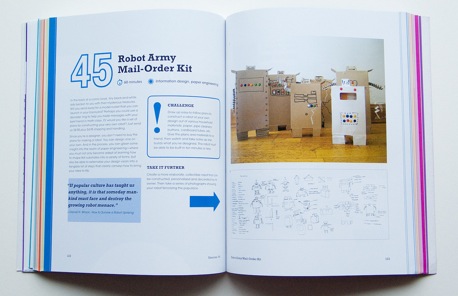

DS: We wrote over 100 challenges. Then, I taught two “80 Works” classes where designers had to solve 80 challenges in an 11-week school quarter. The classes overlapped about 40 of the challenges, and I kept throwing in new experiments to see how they’d fare – as long as they helped to impart the appropriate core skills. The students were also invited to suggest challenge topics, a few of which made it into the book. Additionally, there were challenges that didn’t fit in the classes, so I put out an open call for designers who wanted to try one out for fun. Every challenge that’s in the book has been road tested and gone through a few drafts, just to confirm that it works and there were representative solutions to share. Almost all of the challenges in the book were illustrated by design students or working designers, myself included. In a few cases, the challenge was reverse engineered from amazing student projects and conceptual design projects, and then I tried them out in the classroom.

AP: What were the criteria for selection?

DS: We knew a challenge felt done when we said it didn’t feel “worky,” which was Mary’s slang for just executing a design idea to gain craft and domain skills, rather than forcing the designer to stretch their thinking skills. It’s a book for doing, but you’re not required to fully execute and complete your project in order to gain those core skills. Being allowed to withhold from the final execution of a project in this manner seemed rare in design education.

AP: Why do you feel this is important?

DS: The book is about learning how to think like a designer through making, so we knew that each challenge needed a good reason for being in the book exclusive of making “X” things in a design discipline. What we are really trying to do is get people to see how the thinking and elements of your individual process are connected across all those disciplines. We didn’t want anyone to look at an exercise as being overly output-driven. If you could skip an exercise simply because it wasn’t in your discipline–if it had nothing else to offer other than a finish line–it didn’t go in.

AP: Where they all developed by you or did you manage to collect some from friends, colleagues, etc.?

DS: There’s one in there that were commissioned from Mark Baskinger called “Seeing What Sticks,” and another one by William Bardel called “Bending Geography,” but the rest are original… just my wife and I sitting on the couch, dreaming them up.

In talking to Mark and William during the writing process, I realized that every teacher has their own trove of challenges they use to impart different design skills. There need to be more venues for sharing those kinds of challenges, as they’re an extremely valuable source of knowledge for encouraging how designers grow. And teachers are the ones who best know what range of output each challenge can encourage. There are some books out there that have collected some of these challenges, but many of them are very output driven. I’ve got my hands on some recent books in this vein, like Draw It with Your Eyes Closed: The Art of the Art Assignment, and while the book is fun with regard to the assignments, it’s so visually dry and lacks solutions. For a really difficult challenge, seeing a potential solution can give you the confidence to give it a try, even if it’s far beyond your skill level.

AP: I found some of them very useful for teaching, although I would have loved to have seen more service design challenges in there.

DS: What you’re saying is the feedback from almost any teacher I talk to: “Love the book, I just wish there was more of the discipline that I teach.” It’s kind of like a football coach being frustrated at a cross-training regimen and wishing there were more football scrimmages.

The book’s generalist focus was deliberate. We have to teach skill sets for unique disciplines, but by doing so we often create unintentional silos. The designers I surveyed were griping about the lack of skill in general problem solving, which should be as important across all disciplines.

There’s a gulf between how people talk about “design thinking” and the craft necessary by discipline to execute that thinking. Really great designers know how to extrapolate from their design ideas where and how to execute their ideas, whether it’s a poster or a retail space or a mobile app or a service blueprint.

Otherwise, they’re trapped in one disciplinary vertical, rather than being flexible. We see these boundaries breaking down with the major shift into interactive design from other disciplines, but we risk just training people to be good at making websites and applications rather than being able to explore a problem and solve it through whatever means are appropriate.

I think that any teacher, after having used a number of these challenges, could write their own or extend the set that’s in the book for their own needs or ask their students to create some too. But the book’s designed in a way that’s meant to encourage a way of thinking and doing that isn’t often possible through long-form design projects.

However, I should step outside the initial intent of what the book was intended to do, as I felt exactly like you did when I started teaching storytelling in the California College of the Arts’s BFA in Interaction Design program. I assigned my book as a text, but I could only use a subset of the challenges in the book to support the learning objectives, which focused on storytelling in the worlds of art and in user experience design. I had to create adaptations to extend what’s in the book, then write a pile of new challenges geared specifically towards imparting core storytelling skills. The adaptations seem to be holding up, and the students appear to be having fun.

AP: Since you’ve been using them to teach yourself, which ones have been the hits?

DS: In the first weeks of the class, the hits were ones like “Book Report” and “Imaginary Film.” Though the students were a bit brutalized where we did a follow-on challenge called “Not So Imaginary Film” where they selected their favorite film poster (for Killer Lobsters from Outer Space, from student Cara Kritkos) and had 2.5 hours to conceptualize, film, edit, and render a polished trailer for it. Considering the amount of time they had to pull it off, the work was solid B-movie trashtastic.

AP: How useful do you think they would be outside of a teaching context?

DS: I had initially envisioned the book to be a teaching tool, but my editor at HOW encouraged me from the start of the writing process to craft the challenges for home use first. So while I put a ton of time into seeing if it would work in a class context, that was all in the service of trying to tighten the challenges for personal use. What, you haven’t tried a few at home for fun?

AP: The book is very well and clearly designed, how did this work out between you and Grace Ring?

DS: The process was a perfect example of a writer thinking they know what they want, but the book designer knowing much better how it should be packaged and presented to the reader. I wrote to Grace Ring what I thought the art direction could be for the book, and she responded back to me with a cover solution and overall art direction that was way better than anything I could have imagined!

AP: It’s been out for while now - how has the response been?

DS: The book has been out for about 16 months, and I have found the response overwhelming – much greater than I’d anticipated at the inception of the project. I’ve received feedback from designers that have been using the book at home to hone their skills, managers at companies that use them to teach design skills to their staff, developers that have been working through the book to train themselves design, architects that are using it to teach their staff lateral design skills, design agencies that use them in all-studio meetings to keep the creative juices flowing, and teachers in high schools and colleges worldwide that have integrated the challenges into their overall curricula. Because of all of these different types of people are using the challenges from the book, it keeps getting more attention across audiences that otherwise wouldn’t have had contact with it. Many people are using the Teacher’s Guide that goes along with the book, and I’m looking forward to having some input from teachers about how to improve it. I’ve also been lucky to have taught a lot of workshops across the U.S. about effective brainstorming.

Outside of the U.S., there are also some translations of the book coming out this year. It’s been translated into Traditional Chinese, available for the Taiwanese market. I just got my copy in the mail from Flag Publishing–they were very true to the original art direction from Grace Ring. I’m also waiting with bated breath for the Simplified Chinese translation, which should be out this year in mainland China. I have dreams that someday it will appear in Japanese, Urdu, and German, but so far, no takers.

Also, many people have told me that the book was a good read, which makes me suspicious, as so much of it is meant for doing.

AP: Tell me about your new book, Success by Design: The Essential Business Reference for Designers. Where did the inspiration for this come from?

DS: The idea for the book came from informal group therapy. When I lived in Seattle, every Wednesday night was dubbed “Burger-Drama” - an assortment of friends and refugees from various design studios, agencies and in-house design departments around the Puget Sound region blowing off steam in the middle of their work week at a local bar and grill. Every time we would meet, there would be a point in the conversation where the “cone of silence” would be lowered over the table. While munching on onion rings and drinking IPA beers, we would share the successes, failures, trials and tribulations of running design businesses. No client secrets. No unverified gossip. Just lessons from the school of hard knocks and the occasional story of a crazy co-worker.

Over the first few months of conversation, it became apparent that the majority of our problems had nothing to do with the design work itself. They had to do with being a good businessperson. No matter how many blog posts and books we read, there wasn’t any one in-depth resource we could turn to that would help us answer our recurring questions–and especially not in a fun way!

AP: Do you follow all the tips in your book or did you gather from others?

DS: Much of what is in the book is hard-fought wisdom from my years working as a designer at studios and consultancies, but much of the text could only be written by collaborating with friends in the industry that had experiences that I hadn’t and that were crucial to understanding design as a business. I reached out to some of my former co-workers and friends in Seattle and curated a series of lectures called “Design Business for Breakfast” sponsored by the local AIGA chapter, co-written and delivered with David Conrad, Erica Goldsmith, Fiona Robertson Remley, and a fellow frog that used to live in Seattle, Justin Maguire. These were client service professionals, project managers, studio owners, and creative directors. The lectures were about providing great client service, structuring and managing projects profitably, cashflow management, how to set up a design studio, and design leadership. The series went over really well, and after spending a lot of time with the material and delivering it in person with these collaborators, it felt like it would make a good book. I just knew that it would take a solid year or so to translate the presentations into a 320-page book.

AP: And you’re doing the entire design of this book?

DS: Since I’d designed the lectures, it made sense for me to do the design. I really wanted it to balance in-depth content with visual wit and fun, just like on my blog ChangeOrder. This visual component is lacking in a lot of design business texts, which can be all prose or serious charts and graphs. I think that can be painful for a lot of readers who are visual thinkers.

Grace Ring’s work on my first book book definitely helped me approach designing my second book as cleanly as possible. I would keep saying to myself through the process, “What would Grace do?” Thankfully, she liked how the second one turned out.

AP: How important was it for you to design this yourself and what difference has it had for the writing process?

DS: For this book, it was critical. I ended up doing a major reorganization and rewrite of content once I’d placed it all into layout. I’m a visual person, so once I had a sense what the different chapters were saying to each other, I saw the shape of the final thing and just went for it. Initially, the book had been called Design Business from A to Z and organized in alphabetical order, but the right structure for the book was around major business processes, such as client services, project management, operating your studio, and optimizing your studio.

AP: Do you see this as any way related to Creative Workshop or wholly separate?

DS: Success by Design is quite different from Creative Workshop, even though it’s serving a similar goal: fostering core skills for designers that are often hard to impart through school and professional practice. While my first book was about creativity for designers, Success by Design is about how to build your core skills as a design businessperson. It’s the second book in a trilogy about core skills, but the third I’m going to take a few years to mull over, research, and write. The third book will be about the demons that chase creative thinkers, and though it will touch upon design’s influence on how we live as people, it’s going to be for a more general audience.

AP: Mike Monteiro’s Design is a Job has recently been published to great acclaim. Do you feel you’re covering the same ground or something different?

DS: I haven’t read Mike Montiero’s book yet, so I don’t really know how different or similar they are. You probably know better than me.

“Design Is a Job” is on my recreational reading list along with some new books about design business coming out this year by David Airey, Leah Buley, and Nathan Shedroff, among others. I’m stoked about reading all these books, as each touches on similar content in a unique way. Leah Buley’s is about running a business that provides UX services, for example.

The range of perspectives from these authors speaks to a huge need, and these books are probably just the beginning of a nascent genre. Honestly, there can never be too many books on design business. There are many people out there that I hope will continue to write avidly on the subject, providing and reinforcing crucial information that will help designers run more meaningful and profitable ventures.

In the scheme of things, however, probably my only unique contribution to this genre will have been a preponderance of silly charts.

AP: I think the charts are pretty great actually - a bit of humor goes a long way. So, when is Success by Design coming out?

DS: The book will be out in November 2012. I plan on placing the resources referenced in the book online, such as some worksheets and other tools that can’t fit into the format–that will happen before the book is out, so people get a sense of the content.

Creative Workshop (Amazon US|UK) and Success by Design (available to pre-order on Amazon US|UK) are both published by HOW.

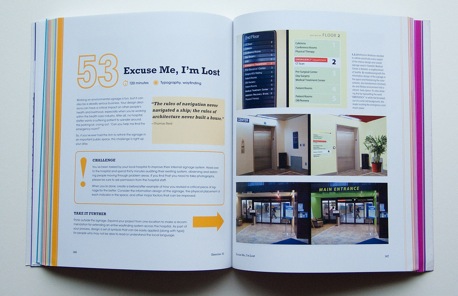

If you would like to support The Designer’s Review of Books purchase them via the links above or The Designer’s Review of Books Amazon store.

About the Reviewer

Andy Polaine is the founder, publisher and now editor-at-large of The Designer’s Review of Books. Apart from that, he is a service designer, writer, lecturer and researcher. He is co-writing a book on service design soon to be published by Rosenfeld Media. You can find his other musings on his own site or as @apolaine on Twitter.