Design Anthropology: object culture in the 21st century

Design Anthropology: object culture in the 21st century, edited by Alison J. Clarke

Publisher: Springer, Vienna, 2011.

Review by Maria Blyzinsky

'This book describes a seismic shift in the way experts and users conceptualize, envisage, and engage in object culture.’

Lofty claims like this always catch my eye because I’m in the business of trying to understand material culture. I work in museums and my curiosity regarding objects is twofold: as something to collect, and as something to interpret. The main thrust of the essays in this collection is an investigation into why objects are designed as they are and how we assign value to them.

Design Anthropology: object culture in the 21st century draws together key thinkers and practitioners from the field of design anthropology - a space where designers and social scientists collide. Social research offers important insights and helps us to understand how we use designed objects to make sense of our everyday lives.

The book is divided into four themes, each with a multi-disciplinary approach to material culture. The reader is taken on a journey, from a design-led approach to understanding objects, through insights from individuals and from corporate points of view, towards a more holistic vision of the future. The essays encourage debate around key design issues and prompt the reader to consider poignant questions such as: What makes an object iconic? Should designers be socially responsible? How does the meaning of an object change according to context? What is the role of vernacular design in the corporate world? How can we design for old age?

The first section presents a grass-roots approach to material culture, focussing on the user for evaluating the effectiveness of a product. In The Designer as Ethnographer, Jo-Anne Bichard and Rama Gheerawo look at the importance of prototyping and user-testing. As a case study, they consider how mobile phones can be adapted for older users.

'The effects of an ageing population… shift the balance of consumer power away from the young towards the older members of society.’

The co-authors reveal valuable lessons about overcoming barriers encountered by older users. Their approach to ‘inclusive design’ can be seen as an important political driver towards attaining social equality.

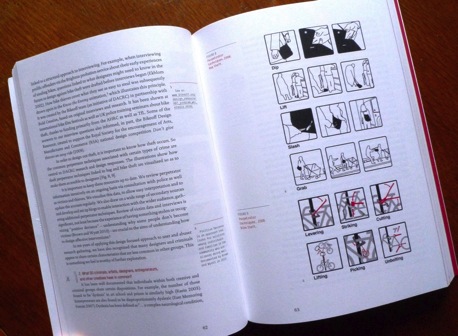

Another essay in the opening section, Criminality and Creativity by Lorraine Gamman and Adam Thorpe, investigates design as a means to deter opportunist theft. Read this and you will never let go of your bag or park your bicycle in a crowded space again.

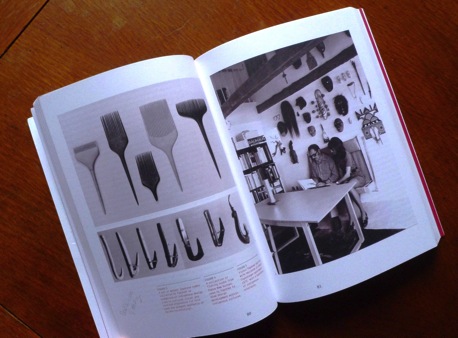

The second section considers what design can tell us about social values. In The Anthropological Object in Design, Alison J. Clarke, editor of the whole volume, considers the emergence of critical design, a movement which grew out of the 1970s when many design practitioners began to question the wasteful culture of capitalism. Clarke’s key subject is the Viennese-born designer Victor Papanek, who took a Darwinist approach to revealing design development. He collected specimens of commonplace objects from different historical and ethnographic contexts, from fish-hooks to hammers, to create an evolution of paraphernalia.

'Papanek combined a nuanced understanding of indigenous material cultures, from Native American to Japanese, with a studied fascination for his culture’s own “exoticism”. He delighted in collecting “idiot gadgets” and socially useless products…’

Papanek was also the godfather of the shift to socially and environmentally responsible design with his now classic, Design for the Real World. He was laughed at when it was first published, but how prescient he was.

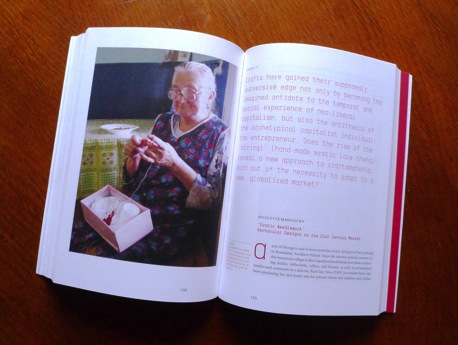

The essays of section three deal largely with materials. In an amusing and erudite piece, Nicolette Makovicky provides an intriguing case study of how a dwindling cottage industry has been revived by responding to modern tastes. Her essay, Erotic Needlework investigates how a group of elderly, Carpathian lace-makers found a new market by creating ‘stringi’, a range of crocheted skimpy underwear.

Despite the popularity of the items and the quality of the needlework, the National Artistic and Ethnographic Commission of Poland has been reluctant to grant the delicately crocheted lingerie the official status of ‘folk art’.

'Virtue and virtuosity, shame and greed became the discourse through which tradition and modernity were discussed as the press feasted on the quaint story of village grannies crocheting racy lingerie.’

The book concludes with a selection of essays which look to the future of design, particularly with regard to the growth of digital technology. In 31m2 and Style, Kathrina Dankle calls for us to resist the idea of ageing as merely a process of decline, but insists that it should instead be considered as one of a range of ‘universal experiences’ associated with life. She persuasively argues for a shift away from specialist objects for the elderly which are purely functional, towards a more aesthetic and sensitive approach where design takes account of personal taste and breadth of experience.

This is an academic and thought-provoking approach to the material world. As well as designers and anthropologists, the volume should be a must-read for anyone with a professional interest in displaying and interpreting objects and collections. The importance of museums as a repository for material culture isn’t lost on the authors, who pepper their essays with reference to a range of international and historic exhibitions to support their ideas: from the Science Museum’s 2004 exhibition, Is this your future?, to Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting held at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York in 2007. Exhibitions by their nature are an ephemeral form of design, so this is an important step towards recognising the significance of the creative practice in its own right.

If there is one omission from the book, it is a museum curator’s approach to the understanding of designed objects. In an essay called Designing Ourselves, Daniel Miller claims that anyone can be a curator. In a sense, he is right because the term has been diluted over the past few years to encompass almost anyone with a passing interest in knick-knacks, a meaning which doesn’t take account of academic rigour or learned expertise. Instead, I prefer his alternative suggestion that anyone can be a designer, because of the many ways we manipulate our physical world, and how this in turn shapes us as human beings.

About the reviewer

Maria Blyzinsky is a museum consultant and freelance curator, as well as a founding member of The Exhibitions Team. She tweets about exhibitions and culture as @MariaBlyzinsky